MDMA

| |

| |

| 臨床資料 | |

|---|---|

| 懷孕分級 |

|

| 依賴性 | 生理: 無 心理: 中等[2] |

| 成癮性 | 中等[3] |

| 給藥途徑 | 舌下 salla |

| 法律規範狀態 | |

| 法律規範 |

|

| 藥物動力學數據 | |

| 藥物代謝 | 肝臟,主要為細胞色素P450氧化酶 |

| 生物半衰期 | 與劑量有關,隨劑量增加而增長,劑量40–125mg時約6–10小時 |

| 排泄途徑 | 腎 |

| 識別資訊 | |

| |

| CAS號 | 42542-10-9 |

| PubChem CID | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| 化學資訊 | |

| 化學式 | C11H15NO2 |

| 摩爾質量 | 193.25 g/mol |

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| |

亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺(3,4-亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺,英語:3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine,簡稱MDMA 屬於苯丙胺類興奮劑,是一種精神藥物,常用作娛樂性藥物。預期效應有增加同理心及欣快感,也會有感覺增強的效果[4][5][6]。若口服的話,藥效會在30至45分鐘後開始,且持續三至六個小時[7][8],有時會用吹藥或是吸食的方式服藥。2017年為止,還沒有MDMA的適應症[9],但在臨床試驗中,它被發現可有效治療自閉症譜系障礙中的創傷後應激障礙和社交焦慮症。

MDMA的不良反應包括上癮、記憶問題、偏執、失眠、磨牙、視力模糊、流汗、心跳過速等症狀[6],使用MDMA也可能會造成抑鬱及疲勞[6]。已有使用MDMA後因為體溫過高及脫水而死亡的案例[6]。MDMA是血清素-去甲腎上腺素-多巴胺釋放劑(SNDRA),也是5-羥色胺、去甲腎上腺素和多巴胺再攝取抑制劑(SNDRI),對大腦中的神經遞質血清素、多巴胺及去甲腎上腺素有釋放作用,也有再攝取抑制的作用,是興奮劑也是致幻效果[10][11]。攝取MDMA後,一開始會讓神經遞質的濃度上昇,之後會有短期的濃度下降[6][8]。MDMA屬於亞甲二氧基苯乙胺衍生物藥物,也是安非他命類藥物。

MDMA在1912年首次製備[6],在1970年代是用在心理治療的輔助使用,而在1980年代開始成為毒品[6][8][12]。MDMA常被認爲和舞會、銳舞、電子舞曲有關[13],而且常混合麻黃鹼、安非他命、甲基安非他命等一起販售[6]。2014年在15至64歲的人當中,使用MDMA的人約有900萬至2900萬人人之間(佔世界總人口的0.2%至0.6%)[14]。此一比例和使用古柯鹼、安非他命類藥物、鴉片類藥物的比例相當,但比使用大麻的人數要少[14]。2010年全美國有90萬人使用MDMA[6]。MDMA經常被用來製作搖頭丸,也是搖頭丸的主要成分之一。

MDMA在大部份國家都不是合法的藥物[6][15],有時為了研究需求,允許有限度的使用[8],目前有研究在探討小劑量的MDMA是否有助於治療嚴重且難治的創傷後壓力症候群(PTSD)[16],美國食品藥品監督管理局在2016年3月允許MDMA的第3階段臨床試驗,探討其效果及安全性[17],並在2017年8月時將MDMA列為創傷後壓力症候群的突破性治療藥物[note 1][21][22]

歷史

[編輯]在實驗室人工合成約兩年後,MDMA在1914年12月24日由德國默克大藥廠申請到專利。當時,默克藥廠有系統地生產合成化學物質,並且大規模地申請專利。這些由默克生產的眾多化學物質都被認為有相當大的潛力,以應用在人類健康方面。MDMA在這眾多合成化學品被遺忘了好幾年乏人問津。

在這期間,MDMA曾被拿來當成食慾抑制劑或是在戰時給士兵的興奮劑[來源請求],隨後發現有嚴重副作用如上癮、引發流血不止、高血壓、心臟病及肌肉壞死等,醫學界才棄用[來源請求],目前,可算沒有一個正式的醫學用途。美國陸軍在1950年代中期曾經對搖頭丸以及其他藥物做了毒性測試。這項研究被叫做EA-1475(EA是Edgewood Arsenal的縮寫)。直到1969年這項研究才被披露。亞歷山大·舒爾金博士是第一位讓亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺被大眾知曉的人,他建議將亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺用在某些療程上,並且把這個藥物取名「窗口」。他發現亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺跟某些肉豆蔻植物內的成份類似,都有影響腦波的作用。心理治療師廣泛地使用亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺(尤其是在美國西岸)一直到80年代被列管才停止。

1980年代中期起,亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺(MDMA)在美國被列為管制藥物。一開始是在德州達拉斯附近雅痞的酒吧裡盛行,然後風行到同志酒吧、電音酒吧,然後躍上主流社群中。1990年代,銳舞電音(rave)起來之時,搖頭丸也開始在大學生以及年輕成年人之間流行起來,最後蔓延到高中生。MDMA很快地就變成美國最被廣泛使用的四種非法藥物之一(其他三種是古柯鹼、海洛因以及大麻)。

娛樂用途

[編輯]台灣常見的稱呼還包括「搖頭丸」、「快樂丸」、「衣服」(取 Ecstasy 第一個字母的發音)、「上面」(衣服是穿在上面的),在香港及南亞等地,這種藥則被稱為「Fing6(揈)頭丸」、「快樂神」、「勁樂丸」、「狂喜」、「迪士高餅乾」等;在其他地區,最常見的稱謂是Molly、Ecstasy(忘我)、Adam(亞當)、Dollar、Fido、Bomb等.

物理與化學性質

[編輯]游離鹼態的MDMA係不溶於水的無色油狀液體。MDMA最常見的存在形式為其水溶性的鹽酸鹽,純淨時呈白色(米白色)粉末狀或晶體狀[9]。

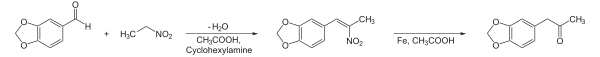

合成

[編輯]MDMA的關鍵前體系3,4-亞甲二氧苯基-2-丙酮(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl-2-propanone),多以胡椒醛及黃樟素為原料製得[23]。現存在多種經黃樟素合成MDMA的路徑[24][25][26][27],其中一種為在強鹼存在下令黃樟素異構化為異黃樟腦後氧化,即得MDP2P;另一途徑則藉由瓦克爾法在鈀的催化下直接氧化黃樟素,其產物經還原胺化轉變為MDMA的消旋體[來源請求]。以溴化氫處理黃樟素後與甲胺加合亦可形成MDP2P。[來源請求]

產量

[編輯]MDMA的生產一般僅使用相對較少的黃樟油。巴西黃樟(Ocotea cymbarum)的精油通常含有80%~94%的黃樟素,因此500ml的精油即能滿足生產150g~340gMDMA的需求[28]。

藥代動力學

[編輯]

神經作用

[編輯]血清素是一種負責控制情緒及快樂的化學物質,許多人[誰?]相信亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺(MDMA)最主要的作用是把腦中的血清素反常地輸送到突觸間隙去。它同時也提升多巴胺以及甲腎上腺激素。這些作用主要歸結於單胺類,SERT(5-羥色胺轉運體)、DAT(多巴胺轉運體)以及正腎上腺素轉運體對亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺(MDMA)的反應[29]。MDMA的化學構型與血清素類似,故能通過SERT,進入serotoninergic neuron中抑制Vesicular monoamine transporter,干擾血清素包入突觸小泡。接著,游離的血清素不再經由胞吐作用進入突觸間隙,而是通過SERT直接進入[30]。多巴胺和正腎上腺素的機制與血清素類似,差異只在於MDMA和多巴胺及正腎上腺素的結構不似血清素相像。

除了一些雜質的危害之外,吸食亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺(MDMA)主要的風險是神精過敏以及脫水。就像安非他明,亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺(MDMA)可能會破壞身體的正常乾渴和精疲力盡等的反應。

長期作用

[編輯]亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺(MDMA)既可以在服用後變得興奮,在藥力過後,亦會使服用者有一種失落感。這是因為藥物影響到大腦對血清素的自然分泌減少所引致的後果,所以若長期服用亞甲二氧甲基苯丙胺(MDMA),可能會引致服用者產生急性或慢性的抑鬱症。然而,有科學家卻認為,我們現時對於情緒及血清素水平的關係還未清晰,而對於血清素在人體內的連鎖反應及代謝過程亦不清晰。[來源請求]

一些實驗表明,持續使用在非常大劑量也許導致5-羥色胺細胞對大腦造成損壞,可能是因為多巴胺被輸入5-羥色胺細胞,再代謝成氫氧化物,造成對5-羥色胺細胞的內部的氧化作用的損傷。這個作用在被老鼠腦子裡做了試驗,當大量的搖頭丸長期被注入體內(通常是人類的一到二倍),動物細胞的5-羥色胺變得凋枯和無用。 [來源請求]

也有些實驗性證據表明長期服用搖頭丸的人將面臨記憶困難。[來源請求]但是,這樣的研究結果受到質疑,原因是食用搖頭丸的人更有可能採取了其他的藥物,甚至濫用的各種各樣的化學製品。[來源請求]

至2007年8月15日,美國科學家證實甲基苯丙胺能降低大腦的生理防禦能力,破壞人體內的膠質細胞衍生營養因子(GDNF),使人容易患上帕金森症和生理上癮。[來源請求]

機體反應

[編輯]

除吸食者想要達到的

其他效果還包含:

- 手汗增加大量出汗

- 心率頻繁及不正常

- 肌肉抽搐

- 語言紊亂

- 脫水

- 頻尿

- 破壞GDNF(人體內的膠質細胞衍生營養因子)

- 凝血障礙

- 高血壓

- 心臟病

- 緊張

- 肌肉壞死

- 精神失常

- 情緒失控

- 記憶減退

- 抑制食慾

- 喪失注意力及專注力

- 疼痛

- 磨牙抽筋

- 腎衰竭

- 上癮

- 神經系統永久損傷

- 血液離子濃度失衡

- 死亡

參考資料

[編輯]- ^ Stimulants, narcotics, hallucinogens - Drugs, Pregnancy, and Lactation, Gerald G. Briggs, OB/GYN News, June 1, 2003.

- ^ 3,4-METHYLENEDIOXYMETHAMPHETAMINE. Hazardous Substances Data Bank. National Library of Medicine. 28 August 2008 [22 August 2014]. (原始內容存檔於2019-04-04).

/EPIDEMIOLOGY STUDIES/ /Investigators/ compared the prevalence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual version IV (DSM-IV) mental disorders in 30 current and 29 former ecstasy users, 29 polydrug and 30 drug-naive controls. Groups were approximately matched by age, gender and level of education. The current ecstasy users reported a life-time dose of an average of 821 and the former ecstasy users of 768 ecstasy tablets. Ecstasy users did not significantly differ from controls in the prevalence of mental disorders, except those related to substance use. Substance-induced affective, anxiety and cognitive disorders occurred more frequently among ecstasy users than polydrug controls. The life-time prevalence of ecstasy dependence amounted to 73% in the ecstasy user groups. More than half of the former ecstasy users and nearly half of the current ecstasy users met the criteria of substance-induced cognitive disorders at the time of testing. Logistic regression analyses showed the estimated life-time doses of ecstasy to be predictive of cognitive disorders, both current and life-time. ... Cognitive disorders still present after over 5 months of ecstasy abstinence may well be functional consequences of serotonergic neurotoxicity of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) [Thomasius R et al; Addiction 100(9):1310-9 (2005)] **PEER REVIEWED** PubMed Abstract

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders. Sydor A, Brown RY (編). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 375. ISBN 9780071481274.

MDMA has been proven to produce lesions of serotonin neurons in animals and humans.

. - ^ Meyer, Jerry. 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): current perspectives. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 2013-11: 83 [2022-03-05]. ISSN 1179-8467. PMC 3931692

. PMID 24648791. doi:10.2147/SAR.S37258. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-07) (英語).

. PMID 24648791. doi:10.2147/SAR.S37258. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-07) (英語).

- ^ Greene, Shaun L; Kerr, Fergus; Braitberg, George. Review article: Amphetamines and related drugs of abuse. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2008-10, 20 (5): 391–402 [2022-03-05]. PMID 18973636. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2008.01114.x. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-22) (英語).

- ^ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 Anderson, Leigh (編). MDMA. Drugs.com. Drugsite Trust. 18 May 2014 [30 March 2016]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-23).

- ^ Freye, Enno. Pharmacological Effects of MDMA in Man. Pharmacology and Abuse of Cocaine, Amphetamines, Ecstasy and Related Designer Drugs. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. 2009: 151–160. ISBN 978-90-481-2447-3. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2448-0_24 (英語).

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 DrugFacts: MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly). National Institute on Drug Abuse. February 2016 [30 March 2016]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-23).

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or 'Ecstasy'). EMCDDA. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. [17 October 2014]. (原始內容存檔於2016-01-01).

- ^ Palmer, Robert B. Medical toxicology of drug abuse : synthesized chemicals and psychoactive plants. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. 2012: 139 [2018-01-05]. ISBN 9780471727606. (原始內容存檔於2020-12-22).

- ^ Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy), National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, [5 April 2016], (原始內容存檔於2016年4月3日)

- ^ Chakraborty, Kaustav; Neogi, Rajarshi; Basu, Debasish. Club drugs: review of the 'rave' with a note of concern for the Indian scenario. The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2011-06, 133: 594–604 [2022-03-05]. ISSN 0971-5916. PMC 3135986

. PMID 21727657. (原始內容存檔於2022-04-01).

. PMID 21727657. (原始內容存檔於2022-04-01).

- ^ World Health Organization. Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence. World Health Organization. 2004: 97– [2018-01-05]. ISBN 978-92-4-156235-5. (原始內容存檔於2020-12-22).

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Statistical tables. World Drug Report 2016 (pdf). Vienna, Austria. May 2016 [1 August 2016]. ISBN 978-92-1-057862-2. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2016-08-09).

- ^ Patel, Vikram. Mental and neurological public health a global perspective 1st. San Diego, CA: Academic Press/Elsevier. 2010: 57 [2018-01-05]. ISBN 9780123815279. (原始內容存檔於2020-09-15).

- ^ Amoroso, Timothy; Workman, Michael. Treating posttraumatic stress disorder with MDMA-assisted psychotherapy: A preliminary meta-analysis and comparison to prolonged exposure therapy. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2016-07, 30 (7): 595–600 [2022-03-05]. ISSN 0269-8811. PMID 27118529. doi:10.1177/0269881116642542. (原始內容存檔於2021-10-28) (英語).

- ^ Philipps, Dave. F.D.A. Agrees to New Trials for Ecstasy as Relief for PTSD Patients. The New York Times. 2016-11-29 [2022-03-05]. ISSN 0362-4331. (原始內容存檔於2017-01-06) (美國英語).

- ^ CBS proclaims ‘cancer breakthrough’ – doesn’t explain what FDA means by that term. HealthNewsReview.org. [2022-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2020-12-08) (美國英語).

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Kepplinger, Erin E. FDA's Expedited Approval Mechanisms for New Drug Products. Biotechnology Law Report. 2015-02, 34 (1): 15–37 [2022-03-05]. ISSN 0730-031X. PMC 4326266

. PMID 25713472. doi:10.1089/blr.2015.9999. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-12) (英語).

. PMID 25713472. doi:10.1089/blr.2015.9999. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-12) (英語).

- ^ Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and. Fact Sheet: Breakthrough Therapies. FDA. 2019-02-09 [2022-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2022-04-27) (英語).

A breakthrough therapy is a drug:

· intended alone or in combination with one or more other drugs to treat a serious or life threatening disease or condition and

· preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over existing therapies on one or more clinically significant endpoints, such as substantial treatment effects observed early in clinical development. - ^ Wan, William. Ecstasy could be ‘breakthrough’ therapy for soldiers, others suffering from PTSD. Washington Post. 26 August 2017 [29 August 2017]. (原始內容存檔於2017-08-29).

- ^ 東邪黃藥師. 美國認可快樂丸中MDMA具高度醫療潛力,可望撫平退伍軍人戰場創傷. The News Lens 關鍵評論網. 2017-09-27 [2022-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2020-12-22) (中文(臺灣)).

- ^ Mohan, J (編). World Drug Report 2014 (PDF). Vienna, Austria: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. June 2014: 2, 3, 123–152 [1 December 2014]. ISBN 978-92-1-056752-7. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2014-11-13).

- ^ Milhazes, Nuno; Martins, Pedro; Uriarte, Eugenio; Garrido, Jorge; Calheiros, Rita; Marques, M. Paula M.; Borges, Fernanda. Electrochemical and spectroscopic characterisation of amphetamine-like drugs: Application to the screening of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and its synthetic precursors. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2007-07, 596 (2): 231–241 [2022-03-05]. PMID 17631101. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2007.06.027. (原始內容存檔於2022-04-22) (英語).

- ^ Milhazes, Nuno; Cunha-Oliveira, Teresa; Martins, Pedro; Garrido, Jorge; Oliveira, Catarina; Cristina Rego; Borges, Fernanda. Synthesis and Cytotoxic Profile of 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“Ecstasy”) and Its Metabolites on Undifferentiated PC12 Cells: A Putative Structure−Toxicity Relationship. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2006-10-01, 19 (10): 1294–1304 [2022-03-05]. ISSN 0893-228X. PMID 17040098. doi:10.1021/tx060123i. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-05) (英語).

- ^ Baxter, Ellen W.; Reitz, Allen B. Reductive Aminations of Carbonyl Compounds with Borohydride and Borane Reducing Agents. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (編). Organic Reactions. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2002-01-09: 1–714 [2022-03-05]. ISBN 978-0-471-26418-7. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or059.01. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-08) (英語).

- ^ Gimeno, P.; Besacier, F.; Bottex, M.; Dujourdy, L.; Chaudron-Thozet, H. A study of impurities in intermediates and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) samples produced via reductive amination routes. Forensic Science International. 2005-12, 155 (2-3): 141–157 [2022-03-05]. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.11.013. (原始內容存檔於2020-10-01) (英語).

- ^ Nov 2005 DEA Microgram newsletter, p. 166 (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館). Usdoj.gov (11 November 2005). Retrieved on 12 August 2013.

- ^ Baker, A.; Lee, N.K.; Jenner, L. Models of intervention and care for psychostimulant users, 2nd Edition, National Drug Strategy Monograph Series No. 51. Canberra. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. 2004.

- ^ MDMA (Ecstasy). Mechanism of Action & Metabolism. [2020-12-29]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-22).

腳註

[編輯]- ^ The FDA's "breakthrough therapy" designation is not intended to imply that a drug is actually a "breakthrough" or that there is high-quality evidence of treatment efficacy for a particular condition;[18][19] rather, it allows the FDA to grant priority review to drug candidates if preliminary clinical trials indicate that the therapy may offer substantial treatment advantages over existing options for patients with serious or life-threatening diseases.[19][20]